Global education:A selection of key charts and trends

Part 4 of 7

Characteristics and behavior of teachers around the world

The recent global expansion of education implied a growing number of teachers across all levels of education.

In many parts of the world the rising number of teachers contributed to reductions in pupil-teacher ratios. Not everywhere though. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the average number of pupils per teacher in primary education is higher today than two decades ago.

In general, pupil-teacher ratios tend to be lower in richer countries. And cross-country differences can be remarkable. In Norway and Sweden there are on average 9 primary-school students per teacher. In the Central African Republic, there are about 80.

About one third of all teachers in the world are primary-school teachers

In most countries, the majority of teachers in primary education are women.

But not in higher levels of education. In fact, in almost all countries the share of women teaching in primary education is much higher than the share of women teaching in tertiary education.

Teacher training and qualifications

Directly measuring teacher quality is difficult. A common approach is to rely on proxies, such as teacher characteristics (e.g. training, qualifications) and behavior (e.g. absenteeism). This map shows the proportion of primary school teachers who are trained to teach. Although the data is patchy, it shows large gaps in some countries. In Ghana, for example, about half of the teachers lack the required pedagogical training.

...and these gaps are also large if we look at subject-specific qualifications rather than general pedagogical training,

In some countries, the share of teachers with training is high but the share with qualifications is low (e.g. Ethiopia). In other countries the opposite is true, and the share of teachers with training is low but the share with qualifications is high (e.g. Niger). And in some countries, such as Ghana and Sierra Leone, both training and qualifications are low.

The scarcity of teacher preparedness means that in some countries there are, on average, up to a hundred students per qualified teacher.

Whether instructors are trained and qualified to teach depends, to a great extent, on the policies and incentives in place. With this in mind, the Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) ranks countries based on whether they have specific policies aimed at preparing teachers with training and experience. In some countries, teachers face little opportunities for professional development. The way education systems select, recruit, train and deploy teachers matters.

Teacher behaviour

Another way to assess teacher performance is to monitor how they work. This is a noisy measure of performance, but it is informative. Random spot checks in schools across several African countries reveal that a large share of teachers are simply absent from schools.

...and even when they are in the schools, teachers are often absent from the classrooms.

...which means a substantial part of scheduled teaching time is effectively lost.

Percentage distribution of estimated effect of selected key resources on student performance – Glewwe and Kremer (2006)

Evidence suggests improving teacher quality is often more effective to improve learning outcomes than increasing the number of teachers per pupil. In fact, Chetty et al. (2014) find evidence suggesting that not only does the entry of a high quality teacher improve the results of students, the presence of ‘bad teachers’ negatively impacts student performance.

Summary of treatment effects from the Teacher Community Assistant Initiative (TCAI) in Ghana – IPA (2014)

However, evidence suggests that improving the quality of teachers is a necessary but insufficient condition to improving student learning in contexts where there are other binding constraints. For example, systems that require teaching an overambitious curriculum are likely to fail independently of teacher skills. This chart summarizes the effects of four different policy treatments within the so-called Teacher Community Assistant Initiative (TCAI) in Ghana. The first two sets of estimates correspond to the test-score impacts of enabling community assistants to provide remedial instruction specifically to low-performing children. These results are consistent with findings from across Africa, suggesting that teaching at the right level causes better learning outcomes in a cost-effective way.

Teacher compensation

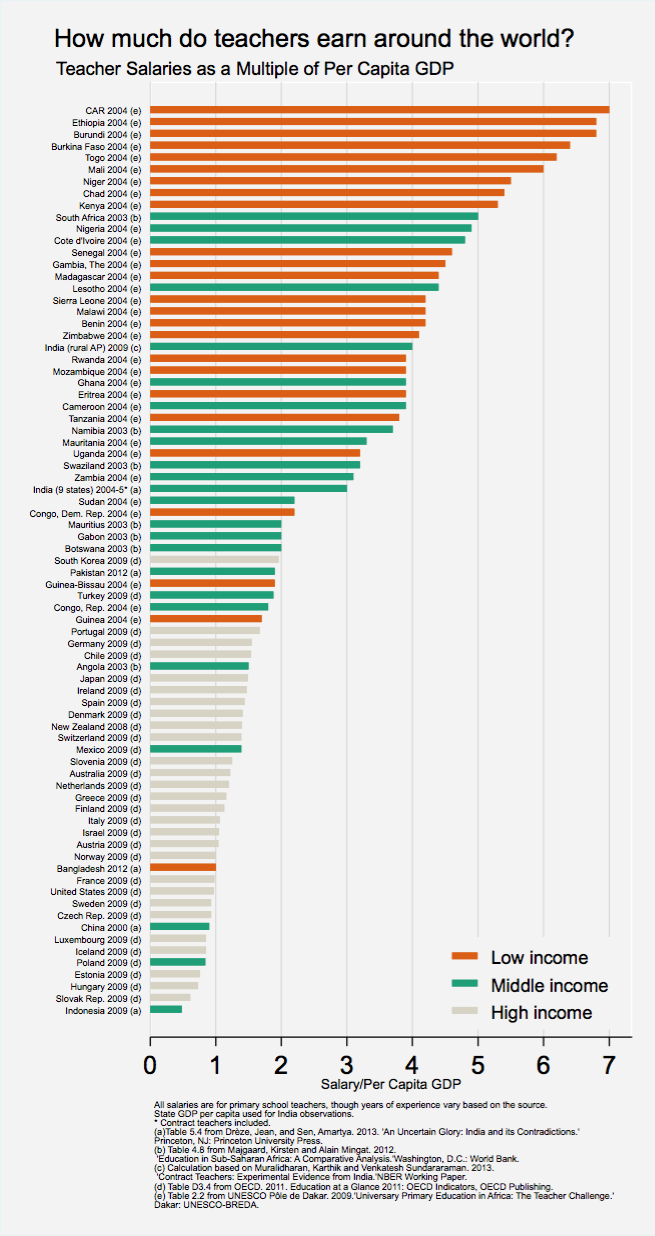

This chart compares teacher salaries across a number of countries with available data. As can be seen, there are very large differences in salaries even among countries with similar income levels.

Teacher Salaries as a multiple of Per Capita GDP – Sandefur (2018)

The previous chart shows teacher pay in absolute terms. Now we show teacher salaries relative to local incomes. As we can see here, relative to local incomes, teachers tend to have higher salaries in poor countries.

If we look at the share of government spending that goes into paying the salaries of staff in public primary schools, we see that there is also large heterogeneity (and no clear regional patterns).

To contextualize these figures, this map shows total government expenditure on education as share of GDP. You can explore similar figures of spending by level in these links: -Pre-primary -Primary -Secondary -Tertiary

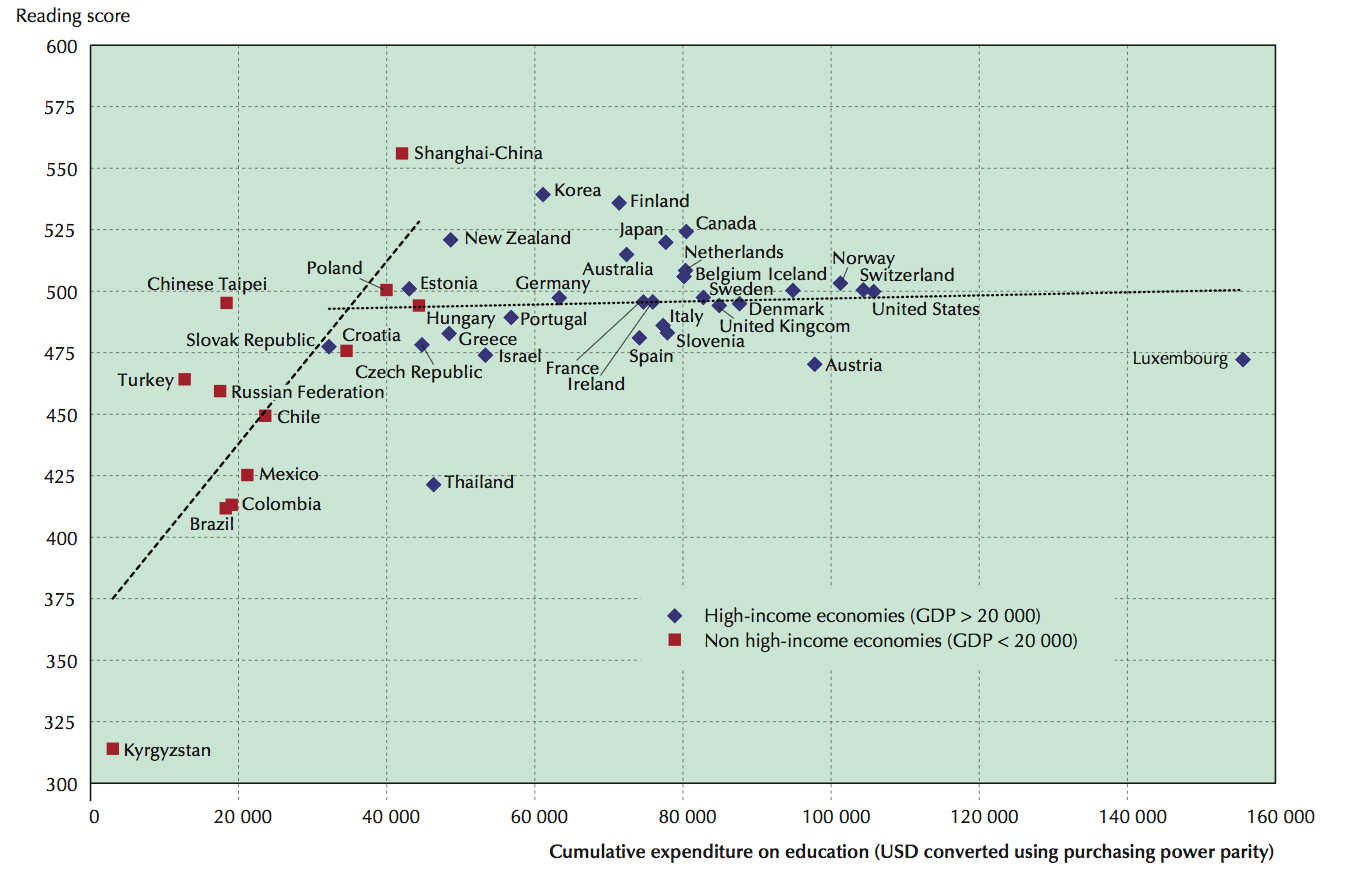

...and this scatter plot shows spending per student in public primary schools in poor and rich countries.

Average reading performance in PISA and average spending per student from the age of 6 to 15 – OECD (2012)

Do countries that spend more per student achieve better outcomes? While there is a positive correlation across non-rich countries, the overall pattern shows that expenditure on education is not, in itself, a good predictor of education quality (Here is an interactive chart with similar data) Figuring out what works to deliver better education outcomes is an important challenge.

Percentage of teachers for whom student test scores are a factor in performance-based pay systems, selected countries – Global Education Monitoring Report (2018)

Many countries use 'performance-based' pay systems that rely on student test scores. Even in countries where the national pay structure does not connect salary with student performance, performance-based pay may indirectly include student test scores as a measure of teacher performance (e.g. Finland).

Evidence from experimental interventions suggests pay-for-performance teacher contracts can improve learning outcomes. But this does not mean that they are necessarily effective at achieving other objectives of time spent in school. In fact, it's important to recognize that mechanisms for increasing teachers’ intrinsic motivation (e.g. professional rewards that increase satisfaction and recognition) may be complementary to extrinsic (e.g. pay-for-performance) incentives. For more on this see the review of the evidence in Glewwe and Muralidharan (2016)

Other resources from Our World in Data

- More slides from this series: ourworldindata.org/slides/Edu_Key_Charts/Menu/ToC.html

- Other articles and resources across related topics: ourworldindata.org/teachers-and-professors ourworldindata.org/financing-education