Global Health

Teaching Notes from Our World in Data

About these Teaching Notes These teaching notes are part of a series of resources from Our World in Data.They have been designed to support those interested in teaching and learning about global development, and they require no background knowledge. Here we touch on the following questions: How does the general health situation of people in poor countries compare to the health of people in rich countries? How are population health outcomes changing over time? How difficult is it to improve health outcomes in poor countries? What does this all mean in terms of policy? For more teaching material visit: ourworldindata.org/teaching-notes

Outline

People in poor countries have much worse health than people in rich countries - We know progress is possible

- Today, a large share of deaths in low-income countries can be prevented

- If prevention is an option, why is it not more common?

- What can be done?

In low-income countries, the average number of years that a newborn infant can expect to live (under current mortality patterns) is much lower than in high-income countries. Life expectancy ranges from just over 50 years in the poorest countries to over 80 years in the richest countries. You can read more about cross-country differences in life expectancy here. (Note: In this interactive map you can use the slider at the bottom to show estimates for any year. And you can click on any country to plot a time series for that country.)

Child mortality is higher in low-income countries. In many countries in sub-Saharan Africa more than 10% of children die before their fifth birthday. In rich countries the corresponding figure is below 1%. You can read more about cross-country differences in child mortality here.

The "burden of diseases", which is a variable that combines mortality patterns with data on the prevalence of disability and illness, also shows that people in poorer countries have generally much worse health. In this map darker colors represent a higher burden of disease. The burden of disease is measured in terms of Disability Adjusted Life Years, or 'DALYs'. One DALY can be thought of as one lost year of healthy life (i.e. a year of life free from illness or disability). You can read more about DALYs and the burden of disease here.

Outline

- People in poor countries have much worse health than people in rich countries

- We know progress is possible

- Today, a large share of deaths in low-income countries can be prevented

- If prevention is an option, why is it not more common?

- What can be done?

Child mortality has declined remarkably in all world regions. And since progress has been faster in the regions with the worst outcomes, we are also seeing convergence: the difference between the best-off and worst-off world regions was almost 30 percentage points in the 1950's and has reduced to less than 7 percentage points today. (Note: In this interactive chart you can click on the option "Add country" to plot numbers for any country or world region. You can also select the "Map" tab to show levels for all countries.)

And it's not just about child mortality. Maternal mortality has also declined across the world. This chart shows the rates of maternal mortality across countries, in the years 1990 (vertical axis) and 2015 (horizontal axis). Countries above the diagonal line have seen improvements. You can read more about maternal mortality here. (Note: In this interactive scatter plot you can click on the continent labels on the right to highlight specific regions. And you can use the option "Search", at the bottom, to highlight specific countries.)

In the long run, the improvements in life expectancy have been large and global. In every country in the world people enjoy a higher life expectancy today than a century ago. (Note: In this chart the x-axis shows the cumulative share of the world population. The countries are ordered along the x-axis ascending by the life expectancy of the population.)

Outline

- People in poor countries have much worse health than people in rich countries

- We know progress is possible

- Today, a large share of deaths in low-income countries can be prevented

- If prevention is an option, why is it not more common?

- What can be done?

HIV/AIDS, Malaria, diarrheal diseases and conditions related to diet (malnutrition, nutritional deficiencies, etc.) are all preventable causes of death. These conditions all rank high among the leading causes of death in low-income countries. (Note: In this interactive chart you can use the option "Change country" to plot the same variables for any country or region.)

Lack of access to clean water affects health even when it doesn't kill you: repeated bouts of diarrhea during childhood permanently impair both physical and cognitive development. This map shows death rates attributed to unsafe water. Roughly speaking, it shows us the number of deaths from drinking unclean water relative to the size of the population in each country. Two cheap “miracle drugs” could already save thousands of children: chlorine for purifying water; and salt and sugar, the key ingredients of oral re-hydration solutions.

Outline

- People in poor countries have much worse health than people in rich countries

- We know progress is possible

- Today, a large share of deaths in low-income countries can be prevented

- If prevention is an option, why is it not more common?

- What can be done?

It's not that people in extreme poverty don't care about their health

People living in extreme poverty do realize that poor health affects the quality of their lives. As this chart shows, people in poor countries have much worse self-reported health status: they are much more likely to say health problems prevent them from doing things they should be otherwise able to do.

Poor people spend a large share of their limited disposable income on health care. Indeed, as this chart shows, a large fraction of health care services in poor countries are purchased directly by households with 'out-of-pocket' resources. But this spending doesn't always translate into effective treatment: In countries such as Nigeria, India, Bangladesh, and Thailand, health care providers without formal medical training account for between one-third and three-quarters of primary care visits.

Most people have a tendency to under-invest in prevention – and this is also true in poor countries

Demand for preventive health care products is very sensitive to prices, even at very low baseline prices. Even small increases in prices can result in a significant fall in take-up rates of basic and effective health measures.

Under-investing in preventive measures can have dramatic consequences when available treatment is deficient

Between October 2002 and April 2003 researchers conducted a cross-country study to measure absenteeism among health providers (doctors, nurses, etc.). This chart shows their results. They found that in India, for example, 40% of health workers were absent from their job at the time of an unannounced spot check. This is evidence of a complicated reality: In low-income countries doctors and health providers in primary health centers are often absent from their job.

As this chart shows, doctors often spend little time with patients.And it's not only about time: in many cases doctors are simply not qualified to do their job. In a test of medical competence for doctors in urban Delhi, a study found that in the majority of cases, formal and informal doctors would recommend a course of action that, based on the assessment of an external expert panel, was more likely to do harm than good. The unqualified private doctors were by far the worst, particularly those who worked in poor neighborhoods (Das and Hammer 2005).

Why demand low-quality treatment and at the same time show indifference toward preventive services?

Lack of information, lack of strategies to avoid procrastination, beliefs held for convenience and comfort in the absence of better alternatives

"The poor seem to be trapped by the same kinds of problems that afflict the rest of us – lack of information, weak beliefs, and procrastination among them. It is true that we who are not poor are somewhat better educated and informed, but the difference is small because, in the end, we actually know very little, and almost surely less than we imagine. Our real advantage comes from the many things that we take as given. We live in houses where clean water gets piped in—we do not need to remember to add Chlorine to the water supply every morning. The sewage goes away on its own—we do not actually know how."

(Banerjee and Duflo, Poor Economics, Page 77)

Outline

- People in poor countries have much worse health than people in rich countries

- We know progress is possible

- Today, a large share of deaths in low-income countries can be prevented

- If prevention is an option, why is it not more common?

- What can be done?

Regulation and macro policies that increase the availability and quality of services are important

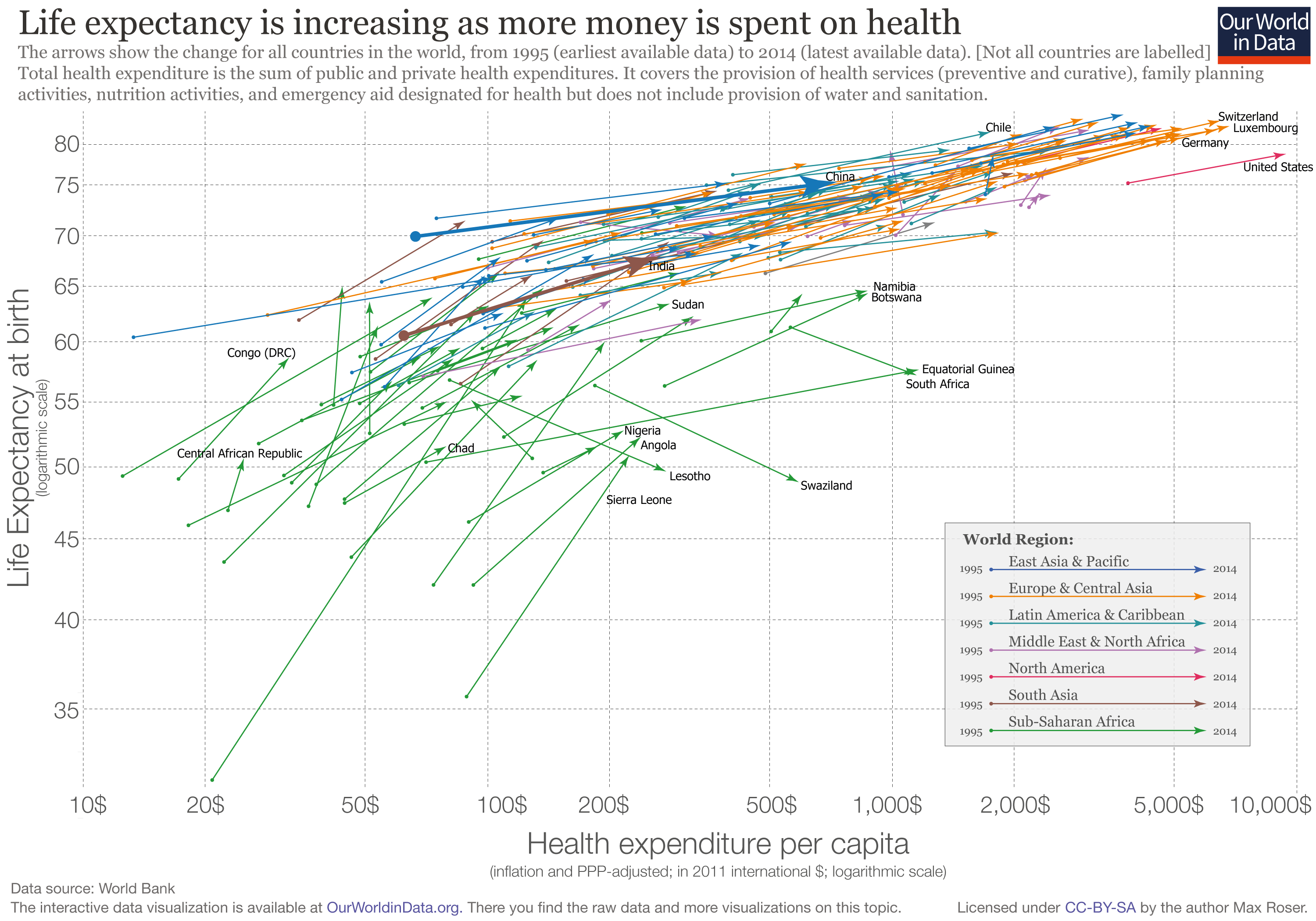

Most countries have increased health outcomes as they have increased spending on health care (and at any point in time, countries with higher spending also tend to have better outcomes). This correlation suggests that structural, macro policies can play a role in improving health outcomes, particularly in poor countries where baseline levels of spending are low. But health care spending is of course not the only driver of health outcomes. In the US, for example, spending has gone up without a substantial improvement in outcomes. You can read more about the link between health care spending and health outcomes here

Vaccination campaigns are a concrete example of a macro-level health intervention that has been shown to work. The WHO estimates that vaccinations today avert 2 to 3 million deaths every year. And historical returns have been huge: Large-scale vaccination campaigns enabled the world to eradicate smallpox. As this chart shows, we went from hundreds of thousands of cases every year, to complete eradication in only a couple of decades. You can read more about the eradication of smallpox here.

Incentives of providers, as well as patient-level interventions are also very important

Small incentives that nudge people to act today, rather than indefinitely postpone, can have large positive effects. Regulation of health providers and subsidies to drastically lower prices can also help substantially.

"We should recognize that no one is wise, patient, or knowledgeable enough to be fully responsible for making the right decisions for his or her own health. For the same reason that those who live in rich countries live a life surrounded by invisible nudges, the primary goal of health-care policy in poor countries should be to make it as easy as possible for the poor to obtain preventive care, while at the same time regulating the quality of treatment that people can get."

(Banerjee and Duflo, Poor Economics, Page 78)

Further Resources from Our World in Data

- Blog posts and data entries on this topic: – ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy – ourworldindata.org/child-mortality – ourworldindata.org/maternal-mortality – ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death – ourworldindata.org/burden-of-disease – ourworldindata.org/malaria – ourworldindata.org/health-meta

- Teaching Notes for other topics: ourworldindata.org/teaching-notes

About the author: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina is an economist at the University of Oxford. He is a Senior Researcher at the Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development. About Our World in Data:Our World in Data is an online publication that shows how living conditions are changing. The aim is to give a global overview and to show changes over the very long run, so that we can see where we are coming from, where we are today, and what is possible for the future. www.ourworldindata.org | @eortizospina